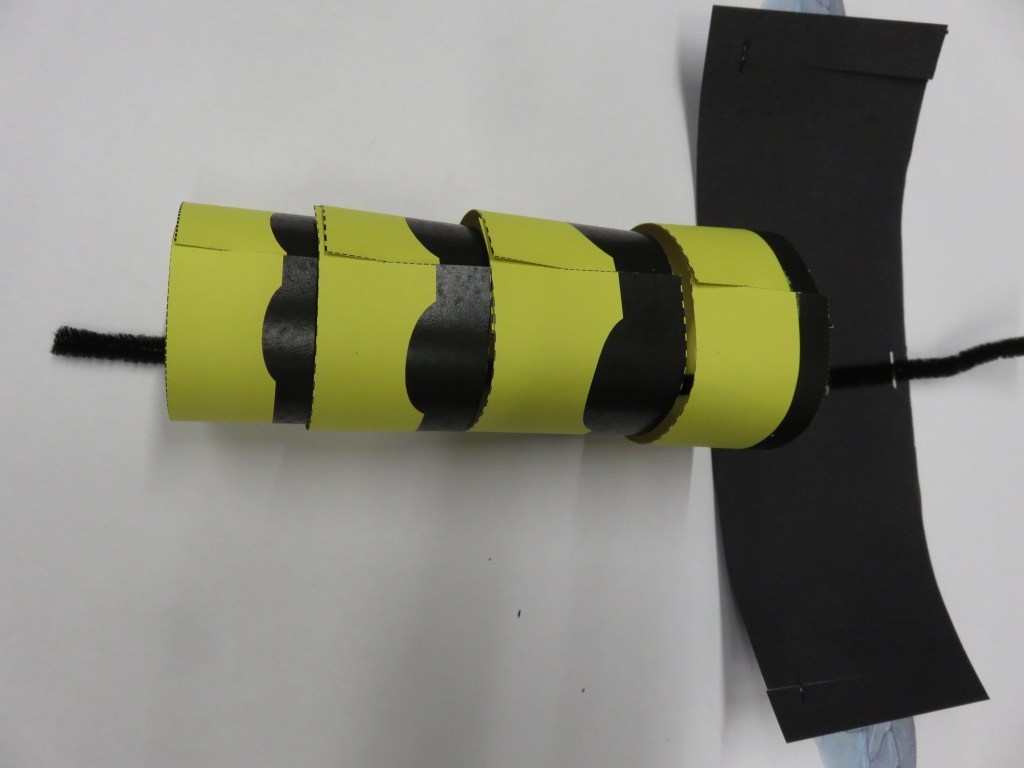

Make a model wasp

At or recent Wonderful Wasps! event, we learned what a diverse group of insects wasps are and how important they are to the environment. We finished by making marvellous model wasps. Here’s a template for making one of your own at home. Some parts of this ‘make’ are a little trick but we think the end result is well worth it!

What you will need

- A print-out of the template. Ideally print the body parts on yellow card but paper will work too. Print the wings onto white paper

- Five black or brown pipe cleaners

- A piece of string, thread or wool

- Scissors

- A stapler

Making your wasp

1 Cut out the pieces.

2 Carefully make cuts in the card as shown by the dotted lines.

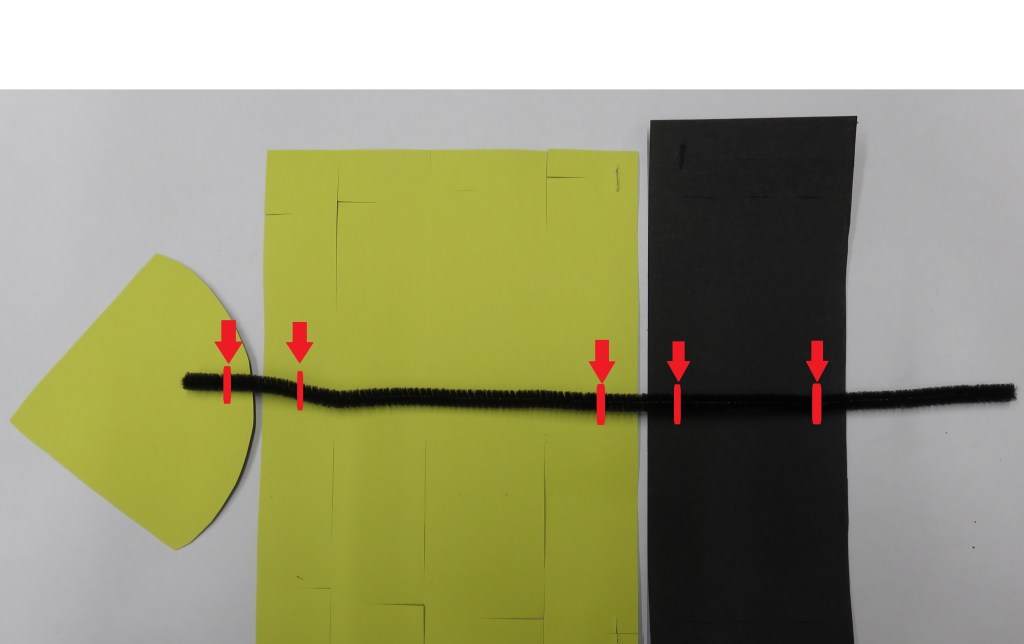

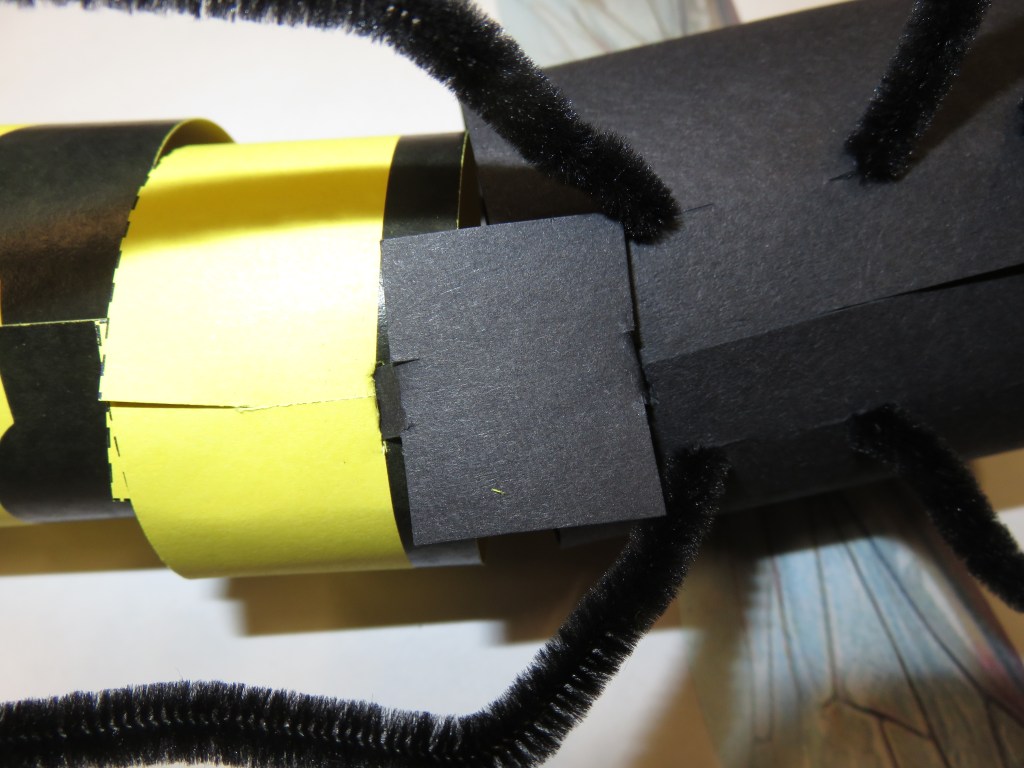

3 Arrange the thorax, abdomen and last segment pieces in a line. Staple a pipe cleaner to these pieces as shown in the pictures below.

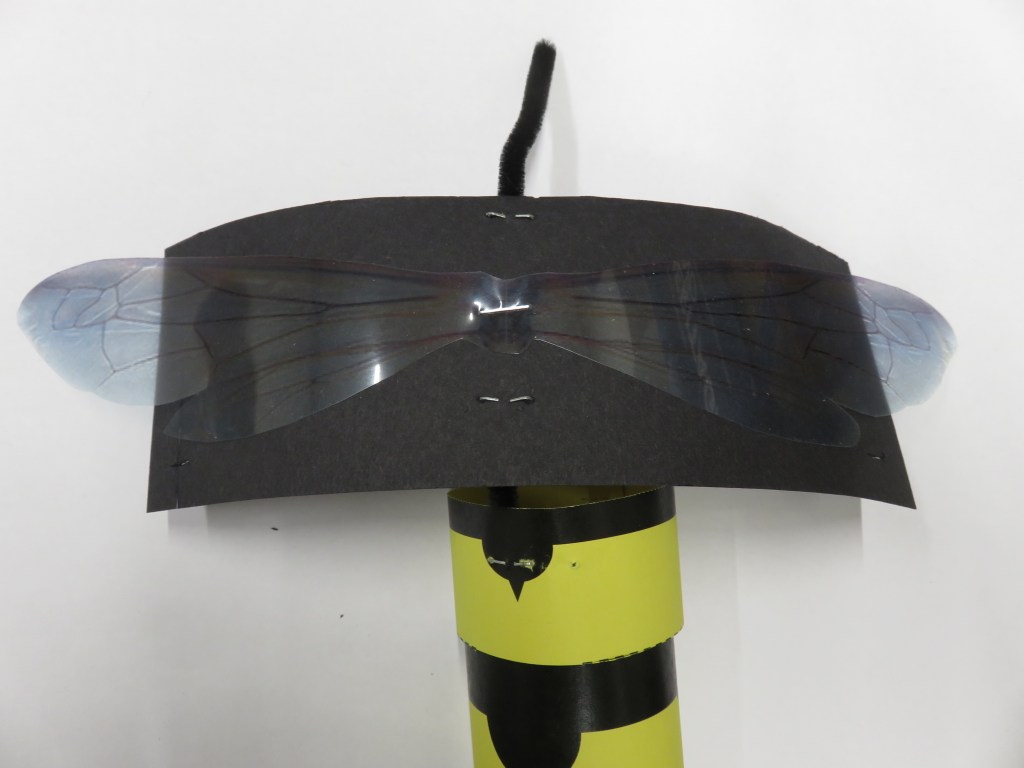

4 Staple the wings onto the thorax.

5 Fold the last segment into a cone shape and secure with a staple.

6 Bend each abdominal section into a circle, slipping the slots together to secure it.

7 Bend the thorax into a circle, slipping the slots together to secure it.

8 Thread 3 pipe cleaners through the holes in the thorax to make 6 legs.

9 Bend the sides of the head together, slipping the slots together to secure it.

10 Staple the bottom edges of the head together

11 Staple the thorax end of the pipe cleaner onto the flap forming the top of the head. Push the end, attached to the tab into the slot.

12 Attach the eyes to the head by pushing the tabs into the slots.

13 Use the waist to connect thorax and abdomen by pushing the tabs into the slots.

14 Tie one end of a string to the pipe cleaner between the thorax and abdomen and the other end between the head and thorax.

Your wasp puppet is now ready!

We hope you enjoyed building your model wasp. When you have finished playing with it, you can use the pipe cleaners for another craft activity and recycle the rest of your model. If you enjoy craft, you might also like to try to try your hand at making an Origami Ladybird.