The Delightful December Moth

The December Moth, Poecilocampa populi, is found all over the UK. Because it is more resistant to cold than most other moths, the adults are common in parks, gardens and woodland during late autumn and winter.

Marvellous Moths

Many people don’t give moths a lot of thought. Most have incredible camouflage and they often fly at night, so we don’t tend to see them. When we do think of moths, it may be just as a kind of drab butterfly that sometimes eats our clothes. In reality, there is much more to the world of moths than we might think, and they are very important to our world.

Moths, together with butterflies, belong to the group of insects called the Lepidoptera (“scaly wings”) There are over 2,500 species of moth in the UK and only a very few will eat our clothes. Many of these moths are beautiful, either because of their spectacular colouration or because of the way their camouflage enables them to blend into their habitat.

Moths are important in ecosystems. Both adult moths and their caterpillars play crucial roles in food chains, feeding on plants and being eaten by bats, birds and other animals. It is estimated that about 35 million caterpillars are eaten by blue tit chicks every year! Moths also play a vital part in the reproduction of several plant species because of their role as pollinators.

‘Like a moth to a flame’

Adult December moths are night-flying and, like other moths, they are attracted to light at night. Entomologists are still not sure exactly why this is. One theory is that moths use the moon to navigate and can mistake a light for the moon. Another is that they normally fly with the lighter sky above them and a light source near the ground confuses them into flying downwards. This would explain why they are attracted to street lights and lit windows, and also why they fly downwards into light traps.

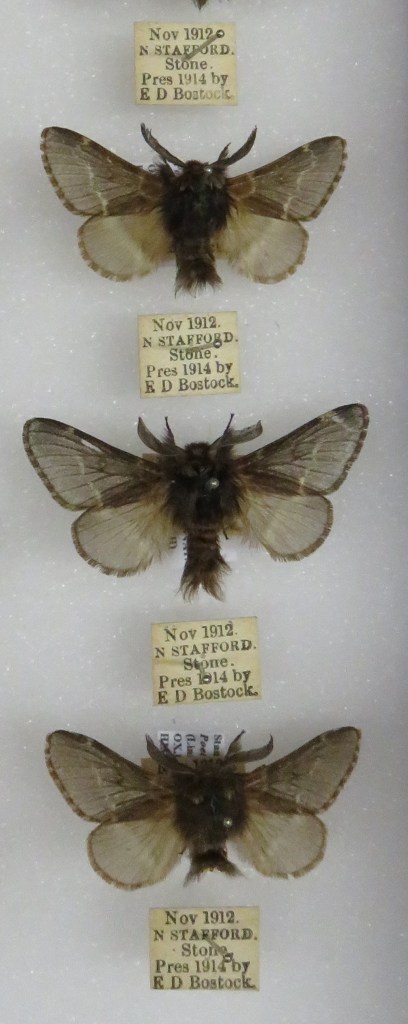

December moth, Poecilocampa populi. Photo: Ben Sale CC-BY 2.0

Life Cycle of the December Moth

While adult December Moths can be found throughout autumn and winter, each individual is short-lived and does not feed. They mate and the females lay their eggs on food plants. The eggs overwinter and the larvae only emerge the following spring. These caterpillars can be found throughout spring and summer taking advantage of the new growth of leaves. They are active voracious feeders at this time and will eat the leaves of a wide range of deciduous trees. When they have gained enough weight, they pupate, with the adult moths emerging to repeat the cycle in late summer and autumn.

Moths are important indicator species: their presence tells us about the overall health of the environment. Unfortunately, what moth populations seem to be telling us is that something is wrong.

Comparing the number and type of moths found in Britain today with those recorded in historic insect collections like the HOPE Collection at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, shows us that moths have declined by about 40% in southern Britain. Over 60 moth species have become extinct in the UK over the last century and many more are at risk of disappearing forever.

Other animal species which rely on moths as food are also suffering, including a decline in bats flying over farmland and reduced numbers of cuckoos, which specialise in feeding on hairy moth caterpillars which other birds tend to avoid.

We need to do more research to fully understand exactly why moth species are declining in Britain, but it is likely to be because of a combination of factors including loss of habitat, farming practices such as clearing hedgerows and the use of pesticides, and climate change.

Adult December moths in the HOPE Collection

Ways we can help moths

Fortunately, many moth species under threat are found in parks and gardens, so we can all do things to help:

- Not over-tidying gardens; a more natural look is much better for insects.

- Growing a wide variety of large and small flowering plants and, if you have room, shrubs and trees.

- Avoiding the use of weed killers and insecticides.

- Reducing light pollution from outdoor lights

- Reducing your carbon footprint, for example, by driving less and walking or cycling more.

If you enjoyed reading about the December Moth, you might like this post by Ben on Raising Poplar Hawk Moths.