Delightful Damselflies

One of the delights of summer is seeing slender bright blue damselflies flying near water. One of the most beautiful is the Azure damselfly, Coenagrion puella.

Dragonflies and damselflies make up the order of insects called the Odonata. Damselflies are members of in the sub-order Zygoptera, meaning “paired-wings”. Dragonflies are in the sub-order Anisoptera, meaning “unequal wings”.

You can tell the difference between damselflies and dragonflies because, in general, the body of damselflies is more slender and delicate compared to that of dragonflies. Damselfly eyes are separated on either side of the head, but dragonfly eyes are often so large they may touch. The forewings and hind wings of damselflies are the same shape, whereas the hindwings of dragonflies are broader than the forewings. Damselflies also tend to close their wings along their body when at rest but dragonflies hold their wings open. Damselflies are not as strong fliers than dragonflies and so may spend more time resting.

Newly-emerged adults are called ‘Tenerals’. They can appear very pale and may not have their mature colouration yet. You may have to look closely for any emerging markings or patterns to help identify it. Very mature adult damselflies can appear much darker.

The Azure Damselfly, Coenagrion puella, is found throughout England and Wales and in Southern Scotland near water, including garden ponds, in which the larvae develop. There is no pupa, instead, the adult develops inside the final larval stage and emerges directly from it. Adults fly between April and September, usually near water. They are about 3cm long and, as their name suggests, the males are banded with blue stripes on their black body, although the females are usually a bright green and black.

The male colouration looks similar to several other blue damselflies but can be distinguished by the pattern, especially on the second abdominal segment. You’ll have to look closely! Try taking a photo and zooming in.

(a) C. puella has a U-shaped black mark on the upper side of this segment.

(b) In the Variable Damselfly, Coenagrion pulchellum, this ‘U’ has a ‘stem’ making it look more like a wine glass.

(c) The Common Blue Damselfly, Enallagma cyathigerum, has a marking shaped like the ‘spade’ on playing cards.

(d) In the Northern Damselfly, Coenagrion hastulatum, which is found in Northern Scotland, the ‘spade’ shape looks more like an arrow head.

(e) The mark on the Southern Damselfly, Coenagrion mercuriale, found in Southern and South-western England and Wales, has ‘arms’ and is sometimes said to resemble a ballet dancer.

Have you seen an Azure Damselfly, or any other type? We would love to hear about it or see your pictures, of these or any other insects. You can get in touch using our Contact Us page.

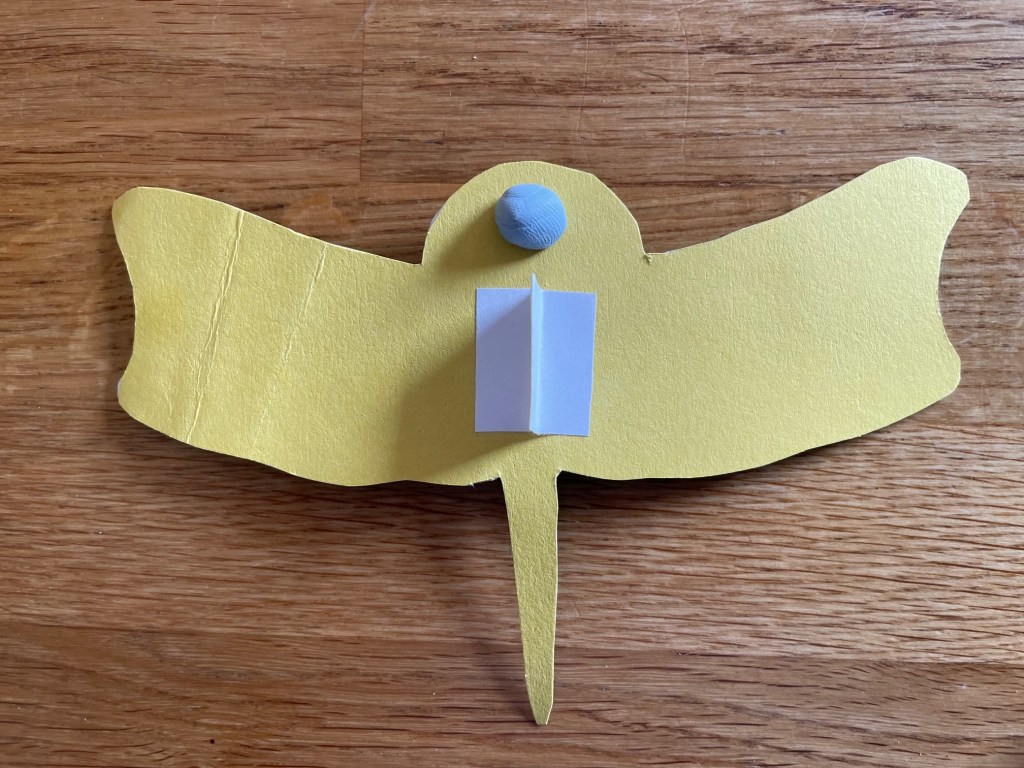

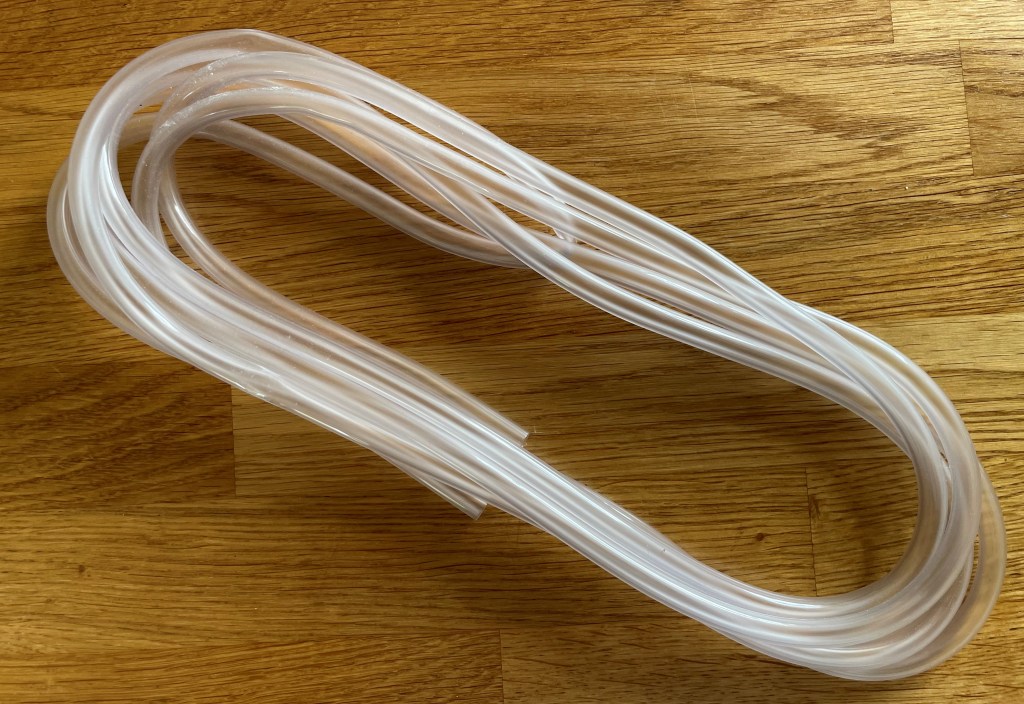

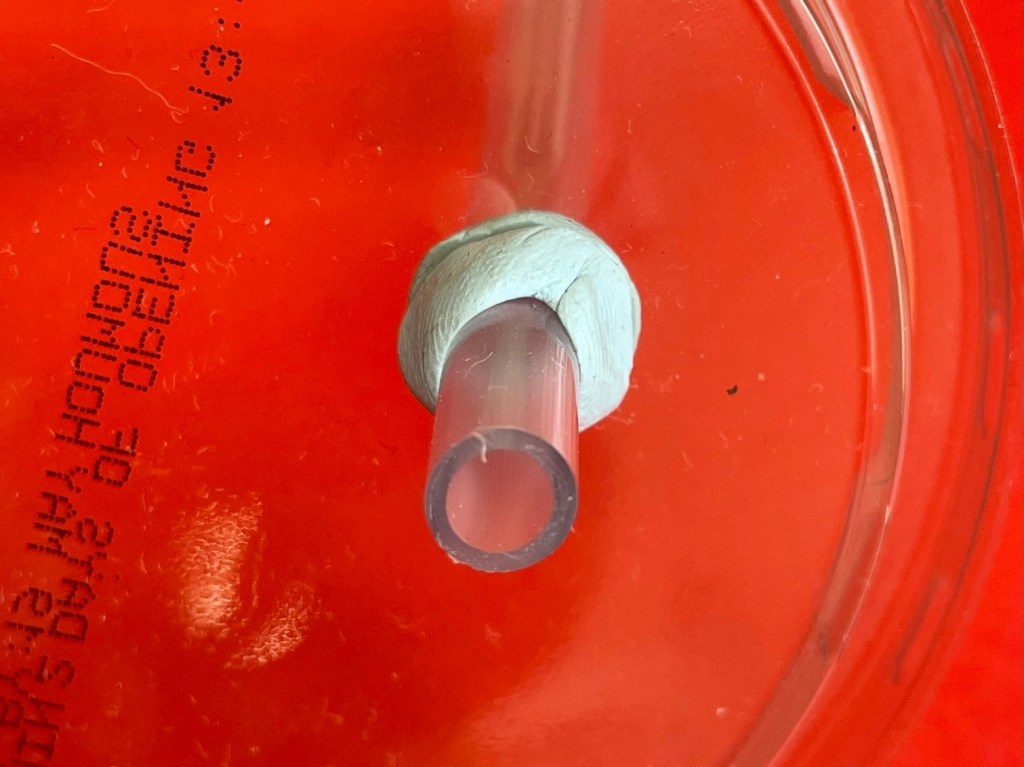

If you enjoyed reading about these insects, you might like to try making your own dragonfly glider.