people: amo spooner

Meet Amo Spooner, Collections Manager for Coleoptera, Hemiptera and Small Orders. Her job, here at the Museum of Natural History, indulges her love of both insect collections and animals in general. I met up with Amo to find out what sparked her interest in the natural world, how she began working at the Museum of Natural History and what her current job involves.

How did you first become interested in insects?

I have always loved the natural world and have a very vivid memory of being woken up in the early morning by my Grandad who wanted to show me some dragonflies emerging from their nymphs in our pond. We rushed out to the pond where dragonflies were pulling their bodies out of the last of their nymph exoskeletons and emerging as adults. I kept the nymph skins as a souvenir and even have a tattoo of an adult dragonfly emerging from its nymph stage to remind me of that time.

How did you come to work in entomology?

After leaving school, I went to college to do a First Diploma and a BTEC National Diploma in Animal Management. At college, I learnt how to care for a wide range of animals from guinea pigs to geckos and helped to run the Exotic Unit. Once I had completed my qualifications, I decided to train as a Veterinary Nurse. It was during the final year of my degree that I first volunteered at the Museum of Natural History and by the time I finished University, I realised that I really wanted to work at the museum, particularly with the insect collection. I moved to Oxford, volunteered at the museum during the day and worked at Waitrose in the evenings to fund my time at the museum.

After volunteering for around 1000 hours, I got my first paid job at the museum! This was working on a collection of entomological specimens that Oxfordshire County Council had donated to the museum. Much of the collection was damaged, but it was possible to save some specimens and incorporate them into the wider museum collection.

What is your role here at the Museum?

I have now worked at the museum for around 11 years and have had several different roles during that time, including re-curating the World Coleoptera collection housed in the Huxley Room. Now, I am on secondment from my Collections Manager role for Coleoptera (beetles), Hemiptera (true bugs) and Small Orders (Dragonflies, praying mantis, cockroaches, lacewings, grasshoppers and allies), leading the collections team responsible for re-curating the British insect collection as part of the HOPE for the Future project.

(See our blog post on Tom Greenway to find out more about this re-curation.)

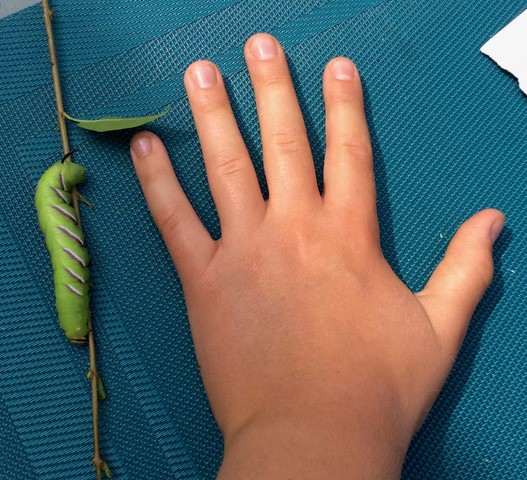

Together with one of my team, I am also responsible for looking after the museum’s collection of live insects and other invertebrates. These include Madagascan Hissing Cockroaches, Tarantulas, Stick insects and a Peacock Mantis. I enjoyed designing and working with an expert to build their new tanks a couple of years ago.

Can you tell us about any particularly challenging aspects of your role?

One of the most challenging aspects of my job is the battle to protect the specimens from insect pests! When live insects infest specimen drawers they can cause considerable damage and it is part of my job to ensure that drawers are checked on a regular schedule to ensure any infestations do not get out of control. This has been particularly challenging during the pandemic when the museum has been closed and access to the collections, even for those of us who work here, has been limited.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I am fascinated by the history of the collections. For example, my favourite entomology collection in the museum is the Baden-Sommer collection which dates back to the early 1900s. It is housed in its original furniture, and is really rich in a wide variety of species, including an incredible number of type specimens. I really enjoy understanding how specimen data labels and pinning techniques have changed over time. For example, when faced with an undated specimen, the handwriting on labels and how an insect is pinned can give you clues about its age. It’s like being an insect detective!

I take great pride and comfort in the fact that my work helps to keep the collection safe for future generations. The work that I am currently undertaking on the British Insect collection as part of the HOPE for the Future project is a great example of this, and will result in the collection being accessible to the public online, and available for teaching and research for many years to come.