Raising Moths

Ben brought in some Poplar Hawk Moths to show the other participants at our recent summer school. Here he describes how he raised them from eggs he received as a gift from his grandfather.

Last year during lockdown my Grandpa gave me 32 hawk moth eggs: 30 eyed and two privet. Not the most common of presents you might think, but these turned into the most enjoyable gift. I was very excited as I tore open the parcel and found the eggs safely packed in a small tube. It took roughly a week for the leafy-green eggs to turn into the most delightful little caterpillars. I decided to call them all Jim. The first thing they went towards was the fresh willow that lay in a small, water-filled jam-jar.

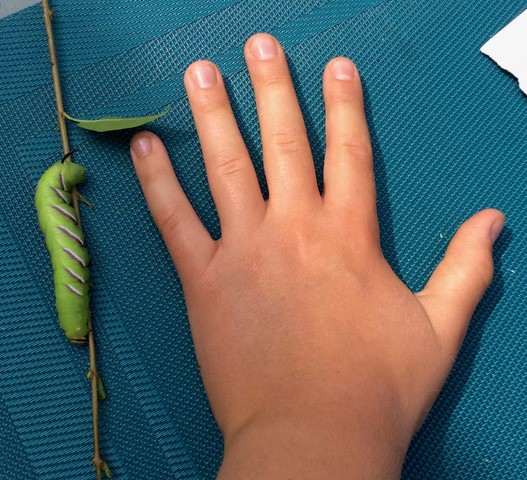

Immediately, they started taking chunks the size of their heads out of the leaves until there were no leaves left inside the tank. I was very surprised by how much they ate in proportion to their size. Every day they grew bigger until, within 4 weeks, they were the length of my index finger! They were bright green with white stripes, pink spots and little pointy tails. To help them grow, they shed their skins every few days. Sadly, one little Jim got stuck in his skin whilst shedding and died. Willow-collecting took a lot of effort as it involved daily trips to the canal, but this was a welcome break from staring at my computer all day during online school.

One morning we found that a lot of the caterpillars were wandering around, banging their heads on the bottom of the tank. They were also turning a darker green which (after a bit of research) we found out meant they needed to bury and become a chrysalis. We put a deep layer of soil into the tank and within minutes they had disappeared. We tucked them up in the shed for winter and waited.

After months of hibernation, they started emerging this spring with crumpled wings, looking very like dead leaves. After stretching out their wings we noticed that we couldn’t see the eyes that the eyed hawk moths are known for, but as we later realised, they only show the eyes as a defence mechanism if they were under attack. Normally it would take a while for the males to seek out the females using their fanned antenna, but because they were in a large tank, it was easy for them to find each other and mate. Within a few days they had laid over 1,000 little green eggs! So, the process of willow collecting began again, but this time, after checking with the county moth recorder, we released the little caterpillars (who this year I called Jeff) into our local wildlife reserve, hoping that they survive and go on to repeat the process in the wild this year.

We are still waiting for the privet chrysalises to hatch, but to keep me busy, my Grandpa sent me 15 poplar hawk moth eggs this spring. These have already been through one cycle of eggs-caterpillars-chrysalis-moth-eggs and I gave some of the eggs to the museum during the Insect Investigators Summer School. I hope the staff have time to collect all that poplar!

The Poplar Hawk Moth, Laothoe populi, is a beautiful insect found thrououghout the UK and is common wherever their foodplants can be found: mainly the poplar trees from which they get their name, aspen and willows. Ben describes the voracious appetite of the larvae well. The adults don’t feed at all and so are short-lived. You can find the adult moth from May to July and the caterpillars from June to October. In Southern England there may be a second generation of adults in the autumn.