A Glorious Grasshopper

The cheerful chirping of grasshoppers on a warm sunny day has been described as the sound of Summer. One species that you are most likely to hear, and see, is the Field Grasshopper, Chorthippus brunneus.

Grasshoppers and their relatives the crickets belong to the insect Order called the Orthoptera. Grasshoppers have short antennae and crickets have antennae which are typically longer than their body. The Field Grasshopper is a common insect and is found throughout the UK. It is well-camouflaged. Its striped brownish colour often matches the grasses among which it lives. The species displays many colour variations, helping it to remain concealed, so you will often hear it before you see it.

Like other grasshoppers, their chirping call isn’t produced by its mouth but by rubbing its back legs against its forewings to make a sound. This is called stridulation. It is the males that make this sound in an effort to attract females. Entomologists often use these sounds to tell different species apart. The ‘song’ of the Field Grasshopper is a series of short ‘chirps’ repeated at intervals. You can listen to it on the orthoptera.org.uk website.

There are a couple of other ways to identify the Field Grasshopper:

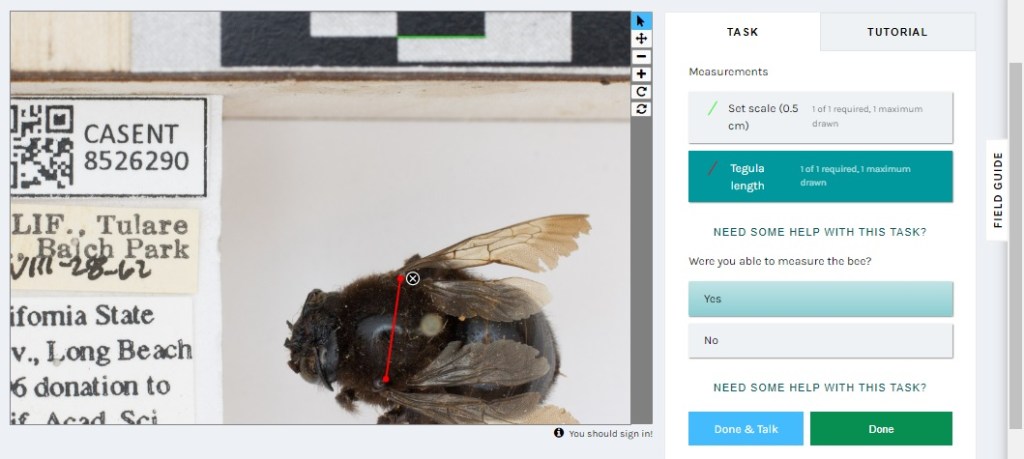

- As you can see in the picture above, the ridges (called keels) at the sides of the saddle-shaped structure just behind the head (called the pronotum) curve inwards sharply in the Field Grasshopper (red arrow). In the similar-looking Meadow Grasshopper (Chorthippus parallelus), the keels are not indented.

- Look at the underside of the grasshopper (if you can catch one!) . In the Field Grasshopper), it looks very hairy. In other similar species it looks smooth.

As their name suggests, Field Grasshoppers can be found in grassland in the countryside and in gardens. They feed on the grasses on which they live. The juvenile grasshoppers start hatching at the end of March. They grow through a series of stages, called instars, with the first adults appearing in June. They live throughout the summer and into late autumn. The females lay eggs in the soil which overwinter, hatching the following spring.

There is still plenty of time this year to spot field grasshoppers so why not have a look in a grassy area near you? We’d love to see any photos you take! If you likes this article, you might also enjoy watching this video about Field Crickets by Professor Karim Vahed.